‘Becoming Human’ Review: A Journey Beyond Cinema

As this year’s Biennale nears its conclusion, its atmosphere begins to transform. The crowds thin, the queues ease, and the audiences lose their initial edge-of-seat tension, settling back into their seats.

‘Becoming Human’ Review: A Deep Dive into Life Beyond Cinema

As this year’s Biennale nears its conclusion, its atmosphere begins to transform. The crowds thin, the queues ease, and the audiences lose their initial edge-of-seat tension, settling back into their seats. Soon, the plaza will be deserted, and the projectors will fall silent.

This setting provides the perfect backdrop to contemplate “Becoming Human” — a tribute to these spaces and their lasting impact on our identities long after the film ends. The debut feature of Cambodian filmmaker Polen Ly, “Becoming Human” is executive-produced by community advocate Davy Chou (“Return to Seoul”) and was developed through the festival’s initiative for emerging filmmakers, Biennale College Cinema. With support from workshops and a €200,000 grant, Biennale College aims to nurture new micro-budget films. This year marks the 14th edition of this initiative.

While the Biennale’s screening rooms are predominantly soundproof, the abandoned Battambang theater at the heart of “Becoming Human” is anything but. The sounds of traffic and pedestrians seep into its auditorium, and rain drips through the deteriorating roof onto the seats below. The screen hangs loosely on one side, cascading to the floor — both alluring and spectral, reminiscent of a flowing vintage dress or a sculptural installation.

In this space wanders Hai (Piseth Chhun). He frequented this theater as a child, back when films were still being screened. Hai approaches this room as if it were a sacred site. Moving to the front of the stalls, he pauses to reflect — singing softly to himself — and lights a cigarette.

He is not alone. A young woman, Thida (Savorn Serak), simply dressed and inviting, appears among the aisles. She informs Hai that she is the guardian of the theater, a role she assumed post-mortem. By remaining the cinema’s guardian, she actively postpones her rebirth into a new life — a process that a debt collector at the door is eager to expedite.

Both Hai and Thida’s homes face destruction — his pagoda, her cinema — and the shadows of the Cambodian genocide loom large in their current lives. Thida must choose: remain with the cinema or embrace a new human life with fresh memories.

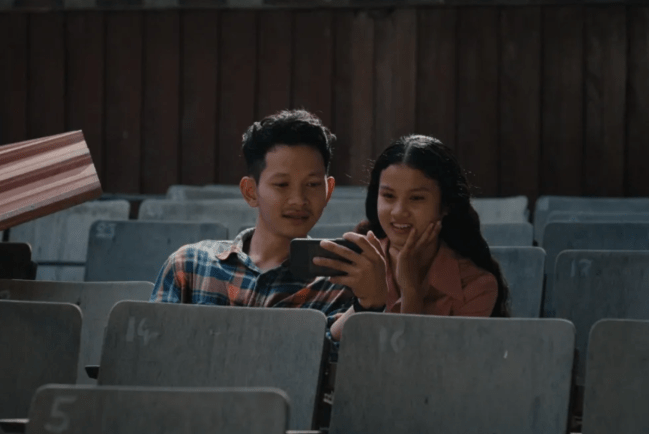

“Becoming Human” distinguishes itself from other cherished works about the decline of cinema spaces (notably “Goodbye, Dragon Inn”) by never showing a film projected there. Instead, the films that Hai and Thida reminisce about are shared in brief clips viewed on Hai’s phone, which they watch side-by-side in the stalls. This is a sweetly pragmatic acknowledgment of our shifting viewing contexts that embraces rather than critiques.

Despite the warmth of their interactions, Chhun and Serak’s dialogue occasionally feels overly scripted, revealing its nature as a performance. While their environments feel richly lived-in, the characters themselves remain somewhat underdeveloped, creating an emotional distance that becomes more pronounced in the film’s latter half. She, the cinema; he, the audience — these archetypes could be compelling in a short format, but in a feature-length film, they rely heavily on the natural chemistry of their performers.

See More ...

If the film’s first act were a standalone short, it would charm and satisfy — Ly’s film establishes its storytelling identity in a confident exploration of place. However, at the thirty-minute mark, we leave the confines of the theater and venture into the world beyond. The Cambodian countryside is captured beautifully, rendered meditative and magical through textured sound design that celebrates the cinema sound systems the film will be presented on.

The narrative shifts focus to her, whoever she may become. The resulting meandering is enjoyable, but much of the initial intrigue dissipates as the film’s unique concept becomes diluted. References to Thida potentially becoming a guardian of another space, an otherworldly being remaining in this world in human form, feel ordinary and mundane. Perhaps, reflecting on the film’s title, that’s the essence. Whether you find these spiritual themes captivatingly elusive or disappointingly trivial will depend on your openness to a cinema that prefers to suggest its world’s rules rather than explicitly define them.

“Becoming Human” seeks to illustrate life beyond the theater, yet its aimlessness can be frustrating. Nevertheless, Ly’s gradual exploration of memory, identity, and place evokes the sensory pleasures reminiscent of Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Tsai Ming-Liang, tapping into the part of the mind that ponders why we gather to watch. A refreshing portrayal of a changing landscape from a new voice eager to leave his mark.

Grade: B-

“Becoming Human” premiered at the 2025 Venice International Film Festival. It is currently seeking U.S. distribution.

Want to stay updated on IndieWire’s film reviews and insights? Subscribe here to our newly launched newsletter, In Review by David Ehrlich, where our Chief Film Critic and Head Reviews Editor compiles the best new reviews and streaming recommendations along with exclusive thoughts — all available only to subscribers.